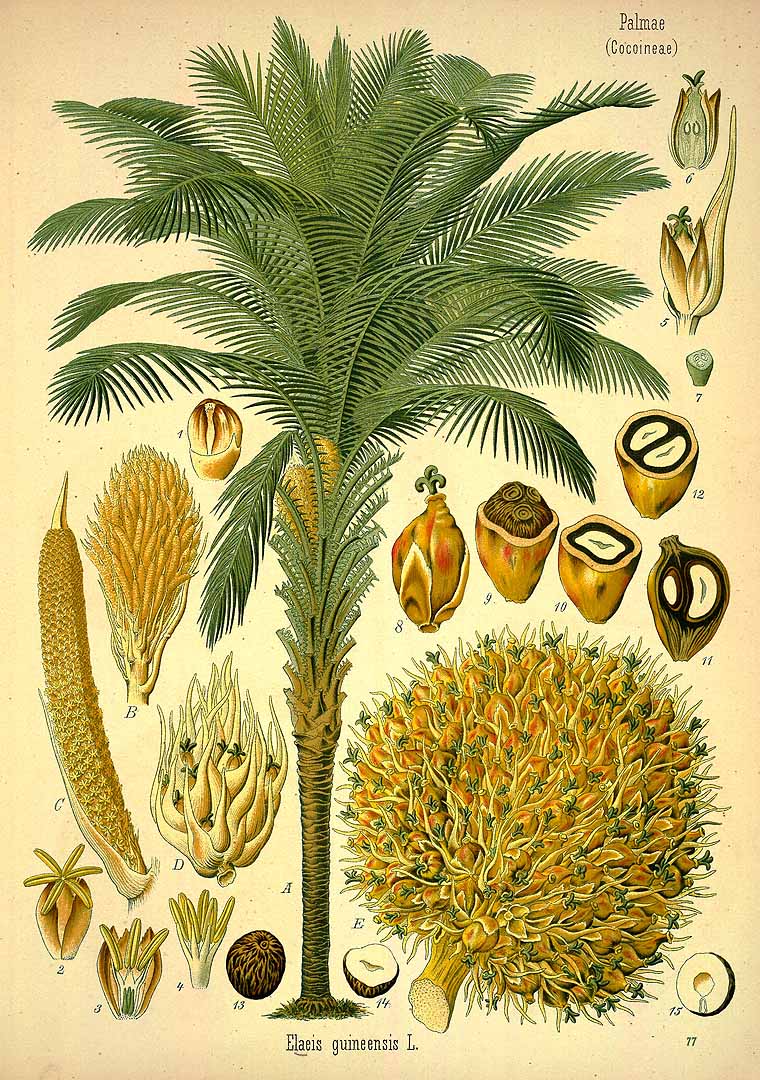

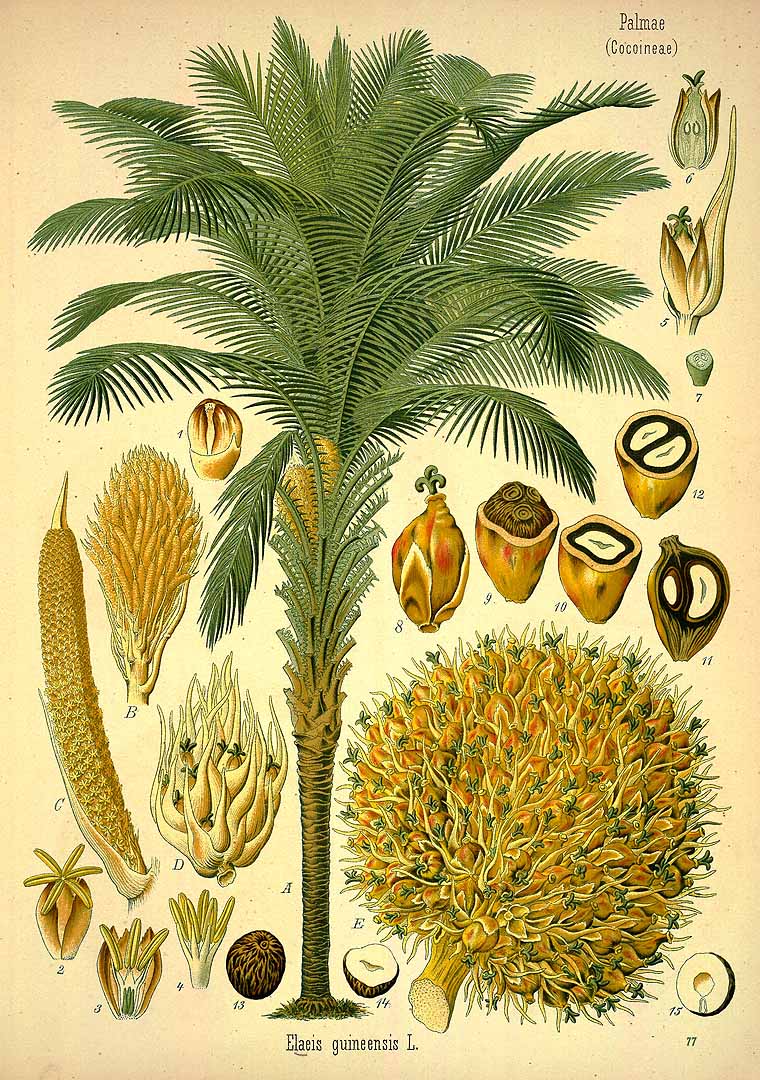

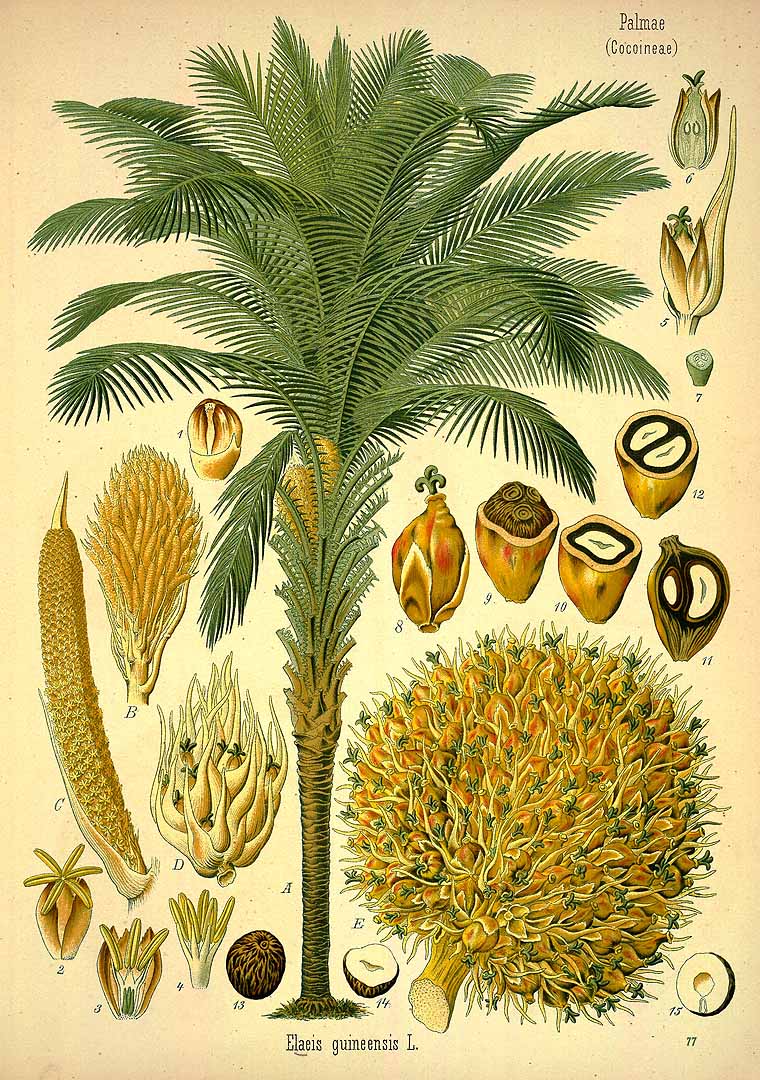

In this fact sheet, we will discuss a plant that, although not Asian, is much talked about in Asia: the Oil Palm. It is a tree 15 to 30 meters high with large palms grouped at the top, the young ones erect, the adults arched falling around the stipe (trunk of the palm trees); they are bordered at the base by about fifty pairs of large thorns. The flowers are monoecious, that is to say that the males and females are separate but present on the same foot. The fruits are made up of large, globular bunches, weighing 10 to 20 kg (or even 70 kg!) and each bearing 1000 to 2000 reddish-yellow drupes. These 3 to 4 cm wide have an oleaginous shell that contains an almond also rich in oil called palm kernel. Two oils are extracted from the oil palm, one is extracted by hot pressing of the pulp of the fruit, it has a beautiful orange-red color; the other is white and extracted from the almond.

Elaeis guineensis, as its name indicates, is native to the west coast of Africa that ancient travelers called “Guinea”. Archaeologists have found traces of this palm tree 3000 years ago and they believe that palm oil was transported to Pharaonic Egypt. As with the Rubber Tree whose history is somewhat the same, the Oil Palm, for economic reasons, was introduced into all humid tropical zones. It appeared on the island of Java in 1848 and from 1911 it was cultivated in Sumatra and then in Malaysia. The English, French and Thai vernacular names remind us that this palm is rich in fat, pam nam man, in Thai, is the translation of “oil palm”. In Cambodian, Vietnamese and Lao, the connection is made with another well-known palm, the Coconut Tree; for the Lao (mak phao ling) is “the monkey coconut tree”, for the Cambodians “the French coconut tree”. The name of the genus itself refers to the Greek and Latin “oil” and “olive tree”.

In Indochina, in 1963, Vidal said that “this introduced palm is frequently observed in gardens where it is planted for ornamental purposes. Its fruits in Laos do not reach maturity and generally abort.” The situation has changed a lot today!

The drama of the Oil Palm is its exceptional productivity reinforced by the creation of many cultivars and its equally exceptional fat content. It provides the most consumed vegetable oil in the world 25%, ahead of soybean oil 24%, rapeseed, 12% and sunflower 7%. This oil is used 80% in the food industry, 19% in cosmetics, 1% for biofuels. It is present in 50% of processed foods for its softness, its long conservation, its low cost. Malaysia and Indonesia represent 85% of world production. In Indonesia, Oil Palm plantations occupy 8.3 million hectares and the government plans to reach 25 million hectares in 2025! The temptation was great in Laos to do as its neighbors and for about ten years Oil Palm plantations have appeared here and there. Adapted cultivars allow this plant to progress well both in the north and the south of the country. The companies that have launched into this exploitation focus mainly on the production of biodiesel, thus masking, under the pretext of sustainable development, the dangers of a devastating culture. Indeed, to have profitable plantations, it is necessary to cut down the primary forest inhabited by men and animals; in Malaysia, entire populations have been sacrificed for short-term profitability. Let us hope that Laos does not follow this example.

Nous évoquerons dans cette fiche une plante qui, si elle n’est pas asiatique, fait beaucoup parler d’elle en Asie: le palmier à huile.

C’est un arbre de 15 à 30 mètres de haut avec de grandes palmes groupées au sommet, les jeunes dressées, les adultes arquées retombant autour du stipe (tronc des palmiers); elles sont bordées à la base d’une cinquantaine de paires de grosses épines. Les fleurs sont monoïques, c’est-à-dire que les mâles et les femelles sont séparées mais présentes sur le même pied. Les fruits sont constitués en volumineux régimes, globuleux, pesant de 10 à 20 kg (voire 70 kg !) et portant chacun 1000 à 2000 drupes jaune rougeâtre. Celles-ci de 3 à 4 cm de large ont une coque oléagineuse qui contient une amande riche aussi en huile appelée palmiste. On tire du palmier à huile 2 huiles, l’une est extraite par pression à chaud de la pulpe des fruits, elle a une belle couleur rouge orangé; l’autre est blanche et extraite de l’amande.

Elaeis guineensis, comme son nom l’indique est originaire de la côte ouest de l’Afrique que les anciens voyageurs nommaient « Guinée ». Les archéologues ont retrouvé des traces de ce palmier il y a 3000 ans et ils pensent que l’huile de palme était transportée jusqu’en Egypte pharaonique. Comme pour l’hévéa dont l’histoire est un peu la même, le palmier à huile, pour des raisons économiques, a été introduit dans toutes les zones tropicales humides. Il fait son apparition dans l’île de java en 1848 et dès 1911 il est cultivé à Sumatra puis en Malaisie.

Les noms vernaculaires anglais, français et thaï rappellent que ce palmier est riche en matière grasse, pam nam man, en thaï, est la traduction de « palmier à huile ». En cambodgien, en vietnamien et en lao le rapprochement est fait avec un autre palmier bien connu, le cocotier; pour les Lao (mak phao ling) est « le cocotier des singes », pour les Cambodgiens « le cocotier des Français ». Le nom du genre lui-même se réfère au grec et au latin « huile » et « olivier ».

En Indochine, en 1963, Vidal dit que « ce palmier introduit s’observe fréquemment dans les jardins où il est planté dans un but ornemental. Ses fruits au Laos n’arrivent pas à maturité et avortent généralement. » La situation a bien changé aujourd’hui !

Le drame du palmier à huile c’est sa productivité exceptionnelle renforcée par la création de nombreux cultivars et sa teneur tout aussi exceptionnelle en matière grasse. Il fournit l’huile végétale la plus consommée au monde 25%, devant l’huile de soja 24%, le colza, 12% et le tournesol 7%. Cette huile est utilisée à 80% dans l’agro-alimentaire, 19% dans les cosmétiques, 1% pour les bio-carburants. Elle est présente dans 50% des aliments transformés pour son moelleux, sa longue conservation, son bas coût. La Malaisie et l’Indonésie représentent 85 % de la production mondiale. En Indonésie, les plantations de palmiers à huile occupent 8,3 millions d’hectares et le gouvernement projette d’arriver à 25 millions d’hectares en 2025 !

La tentation était grande au Laos de faire comme ses voisins et depuis une dizaine d’années des plantations de Palmiers à huile apparaissent çà et là. Des cultivars adaptés permettent à cette plante de bien progresser aussi bien au nord qu’au sud du pays. Les entreprises qui se sont lancées dans cette exploitation mettent surtout l’accent sur la production de biodiesel, masquant ainsi, sous prétexte de développement durable, les dangers d’une culture dévastatrice. En effet pour avoir des plantations rentables il faut couper la forêt primaire habitée d’hommes et d’animaux; en Malaisie on a sacrifié des populations entières à une rentabilité à court terme. Souhaitons que le Laos ne suive pas cet exemple.

In this fact sheet, we will discuss a plant that, although not Asian, is much talked about in Asia: the Oil Palm. It is a tree 15 to 30 meters high with large palms grouped at the top, the young ones erect, the adults arched falling around the stipe (trunk of the palm trees); they are bordered at the base by about fifty pairs of large thorns. The flowers are monoecious, that is to say that the males and females are separate but present on the same foot. The fruits are made up of large, globular bunches, weighing 10 to 20 kg (or even 70 kg!) and each bearing 1000 to 2000 reddish-yellow drupes. These 3 to 4 cm wide have an oleaginous shell that contains an almond also rich in oil called palm kernel. Two oils are extracted from the oil palm, one is extracted by hot pressing of the pulp of the fruit, it has a beautiful orange-red color; the other is white and extracted from the almond.

Elaeis guineensis, as its name indicates, is native to the west coast of Africa that ancient travelers called “Guinea”. Archaeologists have found traces of this palm tree 3000 years ago and they believe that palm oil was transported to Pharaonic Egypt. As with the Rubber Tree whose history is somewhat the same, the Oil Palm, for economic reasons, was introduced into all humid tropical zones. It appeared on the island of Java in 1848 and from 1911 it was cultivated in Sumatra and then in Malaysia. The English, French and Thai vernacular names remind us that this palm is rich in fat, pam nam man, in Thai, is the translation of “oil palm”. In Cambodian, Vietnamese and Lao, the connection is made with another well-known palm, the Coconut Tree; for the Lao (mak phao ling) is “the monkey coconut tree”, for the Cambodians “the French coconut tree”. The name of the genus itself refers to the Greek and Latin “oil” and “olive tree”.

In Indochina, in 1963, Vidal said that “this introduced palm is frequently observed in gardens where it is planted for ornamental purposes. Its fruits in Laos do not reach maturity and generally abort.” The situation has changed a lot today!

The drama of the Oil Palm is its exceptional productivity reinforced by the creation of many cultivars and its equally exceptional fat content. It provides the most consumed vegetable oil in the world 25%, ahead of soybean oil 24%, rapeseed, 12% and sunflower 7%. This oil is used 80% in the food industry, 19% in cosmetics, 1% for biofuels. It is present in 50% of processed foods for its softness, its long conservation, its low cost. Malaysia and Indonesia represent 85% of world production. In Indonesia, Oil Palm plantations occupy 8.3 million hectares and the government plans to reach 25 million hectares in 2025! The temptation was great in Laos to do as its neighbors and for about ten years Oil Palm plantations have appeared here and there. Adapted cultivars allow this plant to progress well both in the north and the south of the country. The companies that have launched into this exploitation focus mainly on the production of biodiesel, thus masking, under the pretext of sustainable development, the dangers of a devastating culture. Indeed, to have profitable plantations, it is necessary to cut down the primary forest inhabited by men and animals; in Malaysia, entire populations have been sacrificed for short-term profitability. Let us hope that Laos does not follow this example.

Nous évoquerons dans cette fiche une plante qui, si elle n’est pas asiatique, fait beaucoup parler d’elle en Asie: le palmier à huile.

C’est un arbre de 15 à 30 mètres de haut avec de grandes palmes groupées au sommet, les jeunes dressées, les adultes arquées retombant autour du stipe (tronc des palmiers); elles sont bordées à la base d’une cinquantaine de paires de grosses épines. Les fleurs sont monoïques, c’est-à-dire que les mâles et les femelles sont séparées mais présentes sur le même pied. Les fruits sont constitués en volumineux régimes, globuleux, pesant de 10 à 20 kg (voire 70 kg !) et portant chacun 1000 à 2000 drupes jaune rougeâtre. Celles-ci de 3 à 4 cm de large ont une coque oléagineuse qui contient une amande riche aussi en huile appelée palmiste. On tire du palmier à huile 2 huiles, l’une est extraite par pression à chaud de la pulpe des fruits, elle a une belle couleur rouge orangé; l’autre est blanche et extraite de l’amande.

Elaeis guineensis, comme son nom l’indique est originaire de la côte ouest de l’Afrique que les anciens voyageurs nommaient « Guinée ». Les archéologues ont retrouvé des traces de ce palmier il y a 3000 ans et ils pensent que l’huile de palme était transportée jusqu’en Egypte pharaonique. Comme pour l’hévéa dont l’histoire est un peu la même, le palmier à huile, pour des raisons économiques, a été introduit dans toutes les zones tropicales humides. Il fait son apparition dans l’île de java en 1848 et dès 1911 il est cultivé à Sumatra puis en Malaisie.

Les noms vernaculaires anglais, français et thaï rappellent que ce palmier est riche en matière grasse, pam nam man, en thaï, est la traduction de « palmier à huile ». En cambodgien, en vietnamien et en lao le rapprochement est fait avec un autre palmier bien connu, le cocotier; pour les Lao (mak phao ling) est « le cocotier des singes », pour les Cambodgiens « le cocotier des Français ». Le nom du genre lui-même se réfère au grec et au latin « huile » et « olivier ».

En Indochine, en 1963, Vidal dit que « ce palmier introduit s’observe fréquemment dans les jardins où il est planté dans un but ornemental. Ses fruits au Laos n’arrivent pas à maturité et avortent généralement. » La situation a bien changé aujourd’hui !

Le drame du palmier à huile c’est sa productivité exceptionnelle renforcée par la création de nombreux cultivars et sa teneur tout aussi exceptionnelle en matière grasse. Il fournit l’huile végétale la plus consommée au monde 25%, devant l’huile de soja 24%, le colza, 12% et le tournesol 7%. Cette huile est utilisée à 80% dans l’agro-alimentaire, 19% dans les cosmétiques, 1% pour les bio-carburants. Elle est présente dans 50% des aliments transformés pour son moelleux, sa longue conservation, son bas coût. La Malaisie et l’Indonésie représentent 85 % de la production mondiale. En Indonésie, les plantations de palmiers à huile occupent 8,3 millions d’hectares et le gouvernement projette d’arriver à 25 millions d’hectares en 2025 !

La tentation était grande au Laos de faire comme ses voisins et depuis une dizaine d’années des plantations de Palmiers à huile apparaissent çà et là. Des cultivars adaptés permettent à cette plante de bien progresser aussi bien au nord qu’au sud du pays. Les entreprises qui se sont lancées dans cette exploitation mettent surtout l’accent sur la production de biodiesel, masquant ainsi, sous prétexte de développement durable, les dangers d’une culture dévastatrice. En effet pour avoir des plantations rentables il faut couper la forêt primaire habitée d’hommes et d’animaux; en Malaisie on a sacrifié des populations entières à une rentabilité à court terme. Souhaitons que le Laos ne suive pas cet exemple.

In this fact sheet, we will discuss a plant that, although not Asian, is much talked about in Asia: the Oil Palm. It is a tree 15 to 30 meters high with large palms grouped at the top, the young ones erect, the adults arched falling around the stipe (trunk of the palm trees); they are bordered at the base by about fifty pairs of large thorns. The flowers are monoecious, that is to say that the males and females are separate but present on the same foot. The fruits are made up of large, globular bunches, weighing 10 to 20 kg (or even 70 kg!) and each bearing 1000 to 2000 reddish-yellow drupes. These 3 to 4 cm wide have an oleaginous shell that contains an almond also rich in oil called palm kernel. Two oils are extracted from the oil palm, one is extracted by hot pressing of the pulp of the fruit, it has a beautiful orange-red color; the other is white and extracted from the almond.

Elaeis guineensis, as its name indicates, is native to the west coast of Africa that ancient travelers called “Guinea”. Archaeologists have found traces of this palm tree 3000 years ago and they believe that palm oil was transported to Pharaonic Egypt. As with the Rubber Tree whose history is somewhat the same, the Oil Palm, for economic reasons, was introduced into all humid tropical zones. It appeared on the island of Java in 1848 and from 1911 it was cultivated in Sumatra and then in Malaysia. The English, French and Thai vernacular names remind us that this palm is rich in fat, pam nam man, in Thai, is the translation of “oil palm”. In Cambodian, Vietnamese and Lao, the connection is made with another well-known palm, the Coconut Tree; for the Lao (mak phao ling) is “the monkey coconut tree”, for the Cambodians “the French coconut tree”. The name of the genus itself refers to the Greek and Latin “oil” and “olive tree”.

In Indochina, in 1963, Vidal said that “this introduced palm is frequently observed in gardens where it is planted for ornamental purposes. Its fruits in Laos do not reach maturity and generally abort.” The situation has changed a lot today!

The drama of the Oil Palm is its exceptional productivity reinforced by the creation of many cultivars and its equally exceptional fat content. It provides the most consumed vegetable oil in the world 25%, ahead of soybean oil 24%, rapeseed, 12% and sunflower 7%. This oil is used 80% in the food industry, 19% in cosmetics, 1% for biofuels. It is present in 50% of processed foods for its softness, its long conservation, its low cost. Malaysia and Indonesia represent 85% of world production. In Indonesia, Oil Palm plantations occupy 8.3 million hectares and the government plans to reach 25 million hectares in 2025! The temptation was great in Laos to do as its neighbors and for about ten years Oil Palm plantations have appeared here and there. Adapted cultivars allow this plant to progress well both in the north and the south of the country. The companies that have launched into this exploitation focus mainly on the production of biodiesel, thus masking, under the pretext of sustainable development, the dangers of a devastating culture. Indeed, to have profitable plantations, it is necessary to cut down the primary forest inhabited by men and animals; in Malaysia, entire populations have been sacrificed for short-term profitability. Let us hope that Laos does not follow this example.

Nous évoquerons dans cette fiche une plante qui, si elle n’est pas asiatique, fait beaucoup parler d’elle en Asie: le palmier à huile.

C’est un arbre de 15 à 30 mètres de haut avec de grandes palmes groupées au sommet, les jeunes dressées, les adultes arquées retombant autour du stipe (tronc des palmiers); elles sont bordées à la base d’une cinquantaine de paires de grosses épines. Les fleurs sont monoïques, c’est-à-dire que les mâles et les femelles sont séparées mais présentes sur le même pied. Les fruits sont constitués en volumineux régimes, globuleux, pesant de 10 à 20 kg (voire 70 kg !) et portant chacun 1000 à 2000 drupes jaune rougeâtre. Celles-ci de 3 à 4 cm de large ont une coque oléagineuse qui contient une amande riche aussi en huile appelée palmiste. On tire du palmier à huile 2 huiles, l’une est extraite par pression à chaud de la pulpe des fruits, elle a une belle couleur rouge orangé; l’autre est blanche et extraite de l’amande.

Elaeis guineensis, comme son nom l’indique est originaire de la côte ouest de l’Afrique que les anciens voyageurs nommaient « Guinée ». Les archéologues ont retrouvé des traces de ce palmier il y a 3000 ans et ils pensent que l’huile de palme était transportée jusqu’en Egypte pharaonique. Comme pour l’hévéa dont l’histoire est un peu la même, le palmier à huile, pour des raisons économiques, a été introduit dans toutes les zones tropicales humides. Il fait son apparition dans l’île de java en 1848 et dès 1911 il est cultivé à Sumatra puis en Malaisie.

Les noms vernaculaires anglais, français et thaï rappellent que ce palmier est riche en matière grasse, pam nam man, en thaï, est la traduction de « palmier à huile ». En cambodgien, en vietnamien et en lao le rapprochement est fait avec un autre palmier bien connu, le cocotier; pour les Lao (mak phao ling) est « le cocotier des singes », pour les Cambodgiens « le cocotier des Français ». Le nom du genre lui-même se réfère au grec et au latin « huile » et « olivier ».

En Indochine, en 1963, Vidal dit que « ce palmier introduit s’observe fréquemment dans les jardins où il est planté dans un but ornemental. Ses fruits au Laos n’arrivent pas à maturité et avortent généralement. » La situation a bien changé aujourd’hui !

Le drame du palmier à huile c’est sa productivité exceptionnelle renforcée par la création de nombreux cultivars et sa teneur tout aussi exceptionnelle en matière grasse. Il fournit l’huile végétale la plus consommée au monde 25%, devant l’huile de soja 24%, le colza, 12% et le tournesol 7%. Cette huile est utilisée à 80% dans l’agro-alimentaire, 19% dans les cosmétiques, 1% pour les bio-carburants. Elle est présente dans 50% des aliments transformés pour son moelleux, sa longue conservation, son bas coût. La Malaisie et l’Indonésie représentent 85 % de la production mondiale. En Indonésie, les plantations de palmiers à huile occupent 8,3 millions d’hectares et le gouvernement projette d’arriver à 25 millions d’hectares en 2025 !

La tentation était grande au Laos de faire comme ses voisins et depuis une dizaine d’années des plantations de Palmiers à huile apparaissent çà et là. Des cultivars adaptés permettent à cette plante de bien progresser aussi bien au nord qu’au sud du pays. Les entreprises qui se sont lancées dans cette exploitation mettent surtout l’accent sur la production de biodiesel, masquant ainsi, sous prétexte de développement durable, les dangers d’une culture dévastatrice. En effet pour avoir des plantations rentables il faut couper la forêt primaire habitée d’hommes et d’animaux; en Malaisie on a sacrifié des populations entières à une rentabilité à court terme. Souhaitons que le Laos ne suive pas cet exemple.